Getting Our Hands Dirty

December 24, 2011

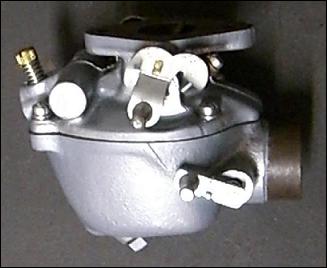

A very nice clean carburetor from a Ford N-series tractor, from MyFordTractors.com. That website, along with Yesterday's Tractors and others like it, make tractor maintenance a lot easier than it would have been prior to the internet. Some might think it bizarre that such recent tools as the internet would make maintenance of these older machines so much easier. Yet information and parts for these old machines has never been easier to access as it is now. For those who love old tractors and implements, whether for show, for nostalgia or for day to day production, these websites are treasure troves of information.

I recently talked about our recent acquisition of an old but sturdy little Ford 9N tractor, which needed some relatively minor work to get up and running again. Since then, I’ve been working on cleaning and rebuilding her carburetor, which was Task #1 for getting her running strong again. That task was one part tedium and one part science project, as I read through several different guides for rebuilding those old carburetors. Happily, the carb rebuild went pretty well, with only two of the numerous jets proving to be difficult to remove. I was able to disassemble, clean and reassemble the rest. Nevertheless, those two jets had to come out and be replaced. So we spent the day yesterday at our mechanic’s shop, learning a few new tricks for getting old jets out of their gunked up threads.

Our afternoon with our mechanic buddy continued to be fruitful, as we reinstalled the carb and continued our troubleshooting work on the 9N’s reluctant engine. We had already cleaned the points on the distributor cap, and now we had a clean carburetor. So why wasn’t the engine running? We tested every spark plug and had good strong regular sparks to every cylinder, and the spark plugs were firing in the correct order. During the moments when the engine ran, we had good compression and a regular rhythm, without any sounds of valves stuck closed or fluttering from excessive wear. What else could it be? Finally, we all looked at each other with a simultaneous moment of “aha!” We opened up the fuel line, and found two things. First, the fuel line itself was apparently plugged with numerous small bits of gunk which resulted in irregular flow to the carb. Secondly, the gas had that characteristically cloudy appearance of stale fuel. Our gas was chemically incapable of burning within the cylinders. But perhaps the worst of all, the tractor's long period of inactivity allowed minute traces of water in the gas to evaporate out, coating the interiors of the tank and fuel lines. Our little tractor needed her pipes cleaned.

Just to test our theory, we ran a flexible tube from a fresh can of gas and fed it directly into the carb intake port. We flushed the cylinders with fresh gas, then turned the engine over again. Our old tractor roared to life and began to purr like a very happy kitten. We had found the problem. We ran her for quite a while from that fresh batch of gas, which helped to flush out any bits of gunk which had passed through the curburetor. I even drove her around a little, with my husband walking alongside holding her fresh gas supply and tube like some sort of IV. Her gears were nice and tight, the brakes braked, the steering steered and everything worked the way it was supposed to. It was a glorious moment. After we ran out of that small batch of clean new gas, we parked her again and went about removing the gas tank for a thorough draining and cleaning. I expect after we get the tank and lines cleaned and reinstalled, then fill our old gal with new fuel, she’ll be the reliable little worker she was designed to be.

Our day was an excellent introduction to the realities of life with farm equipment. Mechanical maintenance and repairs are an ongoing issue within farm management. Every farmer dreads the idea that they’ll be mid-cultivation, mid-planting or mid-harvest, only to suffer a mechanical breakdown. Mechanical function (or the lack thereof) can mean the difference between a bountiful versus failed harvest, particularly for those farmers who are racing to get some task done before nightfall, bad weather or whatever other deadline. Farmers are, understandably, renowned for their mechanical know-how. Yet in recent years that skill-set has been challenged by machines which are dramatically more complex, and more frequently designed to be repaired by a dealer rather than in the farm workshop. When we were shopping for haymaking equipment last summer, one of the biggest recommendations from everyone we spoke to was to find a really good mechanic, because mowers and balers in particular had become so complex. Given that our haymaking window of opportunity can sometimes be measured in mere hours, that mechanical know-how was crucial.

Yet I question the wisdom of getting ever more complex machines which are ever more complex and expensive to fix. That would seem to make timely field operations more difficult to guarantee, rather than more reliable. One of the reasons we went with an older tractor was because we wanted to be able to maintain her ourselves as much as possible, and to limit the costs when something went wrong. For this first foray into the guts of a non-working machine, we were definitely out of practice with our diagnostics. But as our mechanic walked us through the steps he was taking, our previous experience with basic engine know-how came back surprisingly quickly. We were able to keep up with what he was doing and why. Add a few repair and maintenance manuals, and we’re doing most of these repairs now on our own with just the occasional hint or suggestion from the mechanic. While our learning curve for farm equipment is definitely still rather steep, at least we don’t need to go to some intensive factory training seminar to be able to rebuild something.

We knew getting the tractor would bring with it a whole raft of new responsibilities - assessing which parts and systems are in good shape, versus which parts should be replaced, how to find replacement parts, and how to do as much of the work ourselves as possible. In addition, each field operation (at least for now) includes doing functional checks prior to those operations, to ensure the tractor and implements are ready for the task. Furthermore, it means we need to study yet one more topic on top of everything else we already keep track of. It’s not a small task. Anyone doing work on these machines must have both theoretical and practical information about a lot of different systems (combustion, ignition, transmission, electrical, hydraulics, brakes, PTO, etc etc). That education doesn’t come quickly or easily. Many very wise folks suggested that we hire out any tractor work, or rent a newer tractor, rather than buying equipment (particularly such old equipment). There may be days when we recall that advice and think “yea, we should have.” But there is something very satisfying with having our own equipment, having it be basic enough to maintain and repair at least some things ourselves, and taking the time to learn how to do those tasks well. Yes, it’s one more thing on an already busy dance card. But this is another step towards having a truly self-sufficient farm, where we don’t need to hire specialists to get some job done. More to the point, it was the only tractor we could realistically afford. Having the tractor, even an old one, beats doing the same task by hand. No, it’s not perfect - we still need to buy fuel and oil and replacement parts. So maybe instead of one huge leap forward, it’s a few long strides. Still, it’s a move forward. And that’s movement in the right direction.

Winter Growing and Harvesting

December 17, 2011

This photo of frost-covered parsley is from a wonderful blog entry entitled Harvest Winter Greens, on a blog called Throwback at Trapper Creek, written by an author using the pseudonym "MatronOfHusbandry". She writes passionately about four season harvesting and other small-scale farming and self-reliance topics.

We recently began a fairly involved series on the website about how to expand the growing season, which you can read about here. At this time of year, that topic naturally leads folks to wondering about true four-season growing and/or harvesting. Is that possible? Can we actually grow and harvest crops all year around? The short answer is yes, we can. The much more involved answer is: it depends on how much effort you want to put into it. But even there, growers have some options.

There are three issues when growing and harvesting in winter:

1) what temp is the air

2) what temp is the soil

3) how much light is available

Let’s look at those three topics, one at a time.

Air temps are a fairly obvious variable, since we are already painfully familiar with the damage that frost can do to our plantings. Furthermore, many plants will grow very slowly, or not at all, if the air temps are below their preferred temperature zone. Most so-called cool season plants are perfectly comfortable when air temps are between 35F - 45F, but they won’t actually be growing. There is also the issue of daytime/nighttime air temperatures, with some plants appreciating cooler nighttime temperatures. If growing during winter hours, either indoors or outdoors, air temps of at least 45F during the day, and at least 35F at night, and a temperature drop of at least 5F between daytime and nighttime, are probably decent targets for growing conditions.

Soil temperatures, however, are a whole different topic. Here is where folks can actually get into some trouble if they’re not careful, yet even moderate effort yields big results. Soil temperatures are much less variable than air temperatures, and under certain conditions, soil temps are actually easier to control than air temps. This is because "air" as a substance is very hard to warm up and keep warm over time. Soil, however, is much more dense, so it conducts heat much more readily. If that heat can be controlled, growers can provide exactly the right temperatures for their plants. Happily, most plants are very comfortable at soil temperatures which are relatively easy to provide - 50F to 60F is ideal for most garden and crop-type plants. Interestingly enough, soil temps can make a bigger difference to plant growth than air temps. Repeated research findings plus hundreds of anecdotal results in greenhouses around the country (and world) has shown that heating the root zone to ideal temperatures can make a big difference in keeping plants happy and growing. Even when surrounding air temperatures are not similarly warm. Growers can provide an ideal situation by providing both controlled root-zone heat and moderate daytime air temps, while simply ensuring nighttime air temps stay above freezing. For instance, unheated greenhouses can warm enough during the day to raise air temps to 50-70F and keep nighttime temps above freezing. If plants are raised in that climate without root zone heat, cool-season plants would be very happy but warm season plants would grow slowly if at all. But put root zone heat under warm season plants in that same greenhouse, and even tropical plants like peppers can be very happy. See our Season Extender Summary pages for more information on how to provide this extra heat in cost-effective ways.

A third issue which must also be addressed is the amount of light that’s available. Most growers readily rig up some way to provide either heated air and/or heated root zone conditions, then fail to provide sufficient light. There are two criteria for measuring light - the intensity, and the duration. Some growers will provide 24/7 lights, in the form of shoplights over the young plants, and still have growth problems. This common situation arises from several different problems - the intensity of the light (ie, the light is too dim), the duration of the light (which ironically might be too long), and even the light’s wavelength. Let’s look at intensity and wavelength first.

Typical shoplight-type fixtures use fluorescent lights which are enough for us to read by (which is what they were intended for). Yet they don’t provide enough light, and/or light in the correct wavelengths, for the growing plants. This can be remedied by using lights intended for indoor growth, namely, high intensity discharge (HID) lights typically used in hydroponics operations. Of those HID lights, metal halide bulbs are the industry standard for leafy green growth, including preliminary growth in plants destined to flower and set fruit later (such as tomatoes). Metal halide bulbs are specially formulated to release a light bright enough, and in the correct wavelengths, to provide the light needed by that vegetative growth. Some other types of light can alternately be used under some conditions. The new LED lights are very bright, run very cool (so they can be placed very close to the plants without burning them), and are extremely energy efficient. But they are still so new that their purchase price is higher than any other type of light source. The aforementioned shop lights, outfitted with full-spectrum bulbs, are an inexpensive option for germination, the first week or so of growth, and/or sprouting. They too run very cool and can be hung very close to the plants without damage. But as soon as the plants start to grow, they need a higher intensity light source. I have written extensively about HID lights elsewhere on our website. Click here to read more about this topic.

Light duration is a topic which gets into a big more plant physiology than I really want to tackle here. But suffice to say that many plants have very specific needs for certain day length and dark length. These day-length-sensitive plants need a certain amount of dark and light, to allow for correct metabolism. While the “day length sensitive” title would imply that they need a certain amount of daylight, the opposite is true - they need a certain amount of darkness every day. So the grower providing light 24/7 is making it very hard for these types of plants to grow. Again without getting specific, most garden-type vegetables need 12-16hrs of daylight, with the balance in darkness. This makes sense when we remember that sunlight provides fuel, but most growth occurs at night, AFTER that fuel is acquired. This cycle must be preserved if the plants are to grow at optimum rates, which is what all this fuss is supposed to provide. So, whatever light source you use, Dear Reader, make sure you give your plants some darkness too.

So far in this conversation we’ve talked about growth in mid-winter, which would seem to be the goal for growers who want to harvest in mid-winter (or even early spring). But growth isn't the goal - harvesting is the goal. So let's step back and ask whether there might be a way to harvest in four season. Happily for many cool-season plants, there is a MUCH easier way to harvest all year round. Namely, planting a large population of those plants in late summer and/or early autumn, letting them put on growth as the year winds down, then allowing them to go into dormancy over winter. But how does that help us? Easy - we can harvest all through the winter during their dormancy period. We just need to plant enough, early enough, to provide enough harvest material throughout whatever dormancy period our particular climate has. For instance, our region typically experiences first frost relatively late in the year - the second half of October or even early November. Yet we are far enough north that we lose daylight very quickly after equinox. So growers who plant cool-season crops in late August/early September typically has sufficient soil temps and sunlight to provide for excellent growing conditions well into mid-autumn. Just as our day-length is dropping below minimums, those plants have reached near maximum growth anyway. The trick becomes to protect those plants from the ravages of wind, driven rain, drifting snow and repeated frost. A low unheated hoophouse can go a long way towards providing all the protection those plants would need until hard extended freezes come along in late November or early December. Double-layer insulation (row covers over each row, then hoophouses over the top) can protect many plants even in a hard frost. A deep mulch can also be put over the plants, then covered with the hoophouse, to protect plants against even longer cold snaps. As long as the mulch is kept dry, it will provide excellent protection. The trick then becomes digging up/digging out the harvest. Mulches should only be used for extended cold spells, since that mulch will block the light. Even in dormancy, plants need a certain amount of light to stay alive even without growth.

True Confessions

December 10, 2011

A confessional at St. Peter’s Basilica. A familiar sight for Catholics, yet a confessional might seem bizarre to others. The general principle is that “confession is good for the soul”. Not because anyone enjoys admitting that they made a mistake. Rather, because we can heal by sharing our mistakes with others, work on ways to avoid those mistakes in the future, and share what we’ve learned from the experience.

Readers who have been following the blog for awhile will recall that we seemed to drop off the face of the earth in late June of this year, only to re-emerge in early September. At that time, I wasn’t ready, willing or able to write about what had transpired during those missing months. But the time has come to give at least a little bit of info about those two events, provide some cautionary “lessons learned”, and talk about where we’re going from here. But never fear, Dear Reader. The story has a happy ending.

First off, I had a major health scare during June. I won’t say specifically what it was - to borrow a phrase from a friend, “that’s Need-To-Know Info, and folks generally don’t need to know”. I’m happy to say it was not life-threatening, but it had the definite possibility of being life-changing. We knew early in June that *something* was wrong. We just didn’t know what. It took us until late June to figure it out, then another two months to sort out the implications. During that time, there was so much physical and emotional upheaval that we basically cut everything back to a minimum. The health scare itself came and went, but all that followup bloodwork found, amongst other things, some alarming nutritional deficiencies. I was moderately low for a few things like the BComplex vitamins, very low in iron and extremely low in Vitamin D (in summertime, no less!). So I was put on a long list of dietary changes and supplements, and sent on my not-very-merry way.

Then in November I went in for another round of bloodwork. Many of those nutrients came back at OK levels thanks to the dietary changes we’d already made. However, I was still low in iron, and I was even lower than before in Vitamin D. Darnit. Up until that point I had really been hoping that the summer bloodwork was just a fluke. I was feeling better, could work a full day again without completely tuckering out, and my appetite had pretty much returned to normal. But here were the second set of results, with some numbers that were worse than the first go-round. So I got serious about the supplements, started taking extra amounts of iron and Vitamin D, changed my diet even more by adding in a lot more raw foods vs processed items, and then hoped for the best. I wasn’t sure if I’d notice any difference until the next round of blood tests.

Happily, I’ve already had two very interesting developments. First, I’m not cold anymore. I have been an extra-sweater-even-when-it’s-nice-outside sort of person, my whole life. Where folks are wearing shorts, I’ve still got on my sweatshirt or fleece vest. I always wear a hat because otherwise my head gets cold. I always wear socks (even in summertime) because my feet get cold. And I’ve almost always got cold hands. It was something of a joke amongst friends that I was never warm. But it got to be a long haul in winter when warmer temps were very far away. Yet here I was in early December, headed into the cold weather, peeling off layers and turning down the house thermostat. The other thing I noticed was better sleep and more energy. Not hyper energy like after a third cup of coffee. But rather steady energy that lasted well into the evening most days, so that I could get through evening chores without getting cranky. Ok, now I’m a believer. I’m not due for another round of bloodwork for awhile yet, but I’m pretty sure now I’m on the right track.

Lessons learned from this little six-month episode in better nutrition? Our daily food choices really, really matter. When we eat well, and I’m talking nutrient balance, not sheer intake, we can feel years younger. We heal up faster, we stay healthy when everyone else catches the latest cold, and we’re better able to surf the various waves in Life rather than being dragged under. Farmers might be the nutritionist’s worst patients. We tend to think that since we work so hard producing food, we automatically know more than anyone else about how to eat. Folks, take a long hard look in your fridge, and on your plate. The more it’s processed, the less nutrient value it has. And even the best diets might be lacking in this-or-that nutrient (or we need a tad extra for whatever reason). We made changes to our diet this year that seemed difficult at the time, but wow we feel so much better now. It really truly is worth the effort.

As if this summer’s health scare wasn’t enough, the second issue was equally overwhelming: we came to the hard realization that we weren’t bringing in enough money from my work at the other farm. In one of the hardest decisions I’ve had to make in recent years, I told my farming partner at the end of June that I couldn’t continue there. I had to find other work. It was a horrible decision. She took the news very graciously, for which I’ll always be grateful. But then came the next problem - do I re-enter the off-farm workforce or try to launch things here mid-season? We agonized over that one for several weeks. Starting things up here seemed a poor choice - we had piglets on the way but precious little else ready to sell. The off-farm job seemed the wiser decision. I got far enough with the job hunt that I interviewed for several positions which would have paid well, but which also would have had me away from home for 12 hours a day. We basically would have had to shut down the farm, or at least scale back to a fraction of our current size. That is the choice faced by a lot of families today, and we sweated over that one about as much as anyone else would have. In the end I turned down those off-farm jobs. Not because we didn’t need the money, but we weren’t willing to shut everything down to get it. Things looked pretty bleak at that point.

But then, we realized we had another option. Instead of earning more to cover our current rate of spending, we opted to dramatically cut back on our spending so that we could live within our means. Where before we had simply talked about preserving our current operation versus shutting down, this third option meant looking at each part of the farm with a cold hard eye, and figuring out where we were running a cost-effective operation and where we were bleeding money. It also meant putting our household’s finances through the same scrutiny. If we could shave spending enough, that would be the same as me going back to work, without the downside of me commuting into town and being gone all day. Now that was worth some consideration.

Towards that end, we enrolled in a series of classes known as Financial Peace University, created by financial consultant Dave Ramsey. In those classes, we made huge strides in identifying how much we spend on various categories during any given month, and how that distribution compares to “healthy” spending ratios. Ratios which help build savings, eliminate debt, ensure retirement funds and allow for charitable donations. It was simultaneously refreshing and demanding to go through those classes, learn where we’d been headed off-track, and learn how to get back on-track. Happily, as part of those classes, we determined that we can definitely live within our means and keep the farm going, IF we are careful with our budgeting and spending.

We are still discussing whether or not I am going to take on some additional part-time work to help improve the budget. I made the decision earlier this year to work at another farm, in large part because our own farm wasn’t far enough along in development to provide sufficient income. We’re earning money but we’re also still under construction in many ways. That continued development costs money up front, well before we see related earnings. Furthermore, investing in labor-saving equipment such as Dorothy, will save us money in the long run but cost money up front. So we either save up and acquire those things slowly with our current earnings, or save up and acquire them faster if we have more income rolling in. That math means I’ll probably be doing at least some part-time-work in 2012. Whatever we decide about additional part-time income for me, we know now that we can live within our means, take care of emergencies that come up, and continue to build the farm into reaching its full potential. And that’s a very comforting thing to know.

So, Dear Reader, in 2012 we have our work cut out for us. Preserve the momentum we’ve built in both personal nutrition and personal finance, and use that momentum to help carry us farther along in our chosen work. For awhile this summer we really thought perhaps the farm was just too expensive for us to continue. Since then we’ve learned that letting the farm go would be even more expensive, in terms of what we’d lose and the lifestyle we’d leave behind. That simply wasn’t acceptable to either of us. So we go into 2012 with most of the same goals we already had, but a few more tools in the toolbox with which to achieve them. Not a bad place to be at all.

A New Old Friend

December 4, 2011

A very attractive Ford 9N featured on Arthurs Tractors, painted in the traditional Ford all-gray 9N color scheme. Ours isn’t nearly so pretty, having been spray-painted a gawdy silver color. Regardless of the paint scheme, the 9N is a solid little tractor which was designed to do a variety of tasks on small family farms - perfect for our tasks. For more information on the Ford 9N and the other N series tractors, please visit 9nford.com, Old Ford Tractors History page, NTractorClub.com, and n-news.com.

Yesterday we did something which I only recently decided we wouldn’t do. We bought a tractor.

Not just any tractor. A 1939 Ford 9N. Most farmers we know would laugh to learn that we had agonized over whether to get a tractor for haying and the various other tasks we have around the farm, only to end up with a tractor that is ancient by most measures, underpowered and unsophisticated when compared to most modern models. Even tractors only ten years younger feature now-standard items such as live PTO, sturdier front ends and better hydraulics. Nevertheless, here we are, owners of a new-to-us little helper with a big heart.

So why on earth would we decide to get a tractor after concluding we didn’t want one? First, you may recall my recent blog entry here about deciding that we needed haymaking equipment, and that we preferred to train up our horses rather than buy a tractor for the same job. Since that blog entry, we have spoken to several well-respected work horse trainers who have impressed upon us that our goals are achievable, but probably not in time for the 2012 haying season. Secondly, there are tasks around the farm which horses just can’t quite help us with. First and foremost on that list, ironically, is the handling and transport of horse manure, and moving the related compost materials from stall to bin to field. While manure spreaders are definitely still a valid use of living horsepower, I have never seen a good setup for using horses to strip down a barn, move raw manure to the compost bin, turn the bin, and then move the contents into the spreader. To date my shoulders and I have been the lucky workers in that particular chain of events. While I appreciate the upper body strength I’ve developed as a result, I can’t pretend that my shoulders can take that kind of workload forever. Third, there is something to be said for having any form of PTO on the farm, with wheels to bring it to wherever it’s needed.

So late at night when no one was looking, I continued the search for a tractor. I told myself that I was just “keeping my finger on the pulse of the local market”, but really I was waiting for The Perfect Machine to magically appear. It had to be that nearly impossible combination of well-equipped yet dramatically inexpensive tractor, capable of doing the work we wanted it to do yet also fitting into our very restricted budget. Up until now, I had never found a tractor that met those criteria. Then a week ago (the day after Thanksgiving to be precise), I found the Craigslist ad for a 9N with a lot of new parts, equipped with a front end loader, for a price we could deal with. I couldn’t believe my luck.

My first thought was “something is wrong with it.” I had to proceed carefully, lest wishful thinking take over. I called the seller, and asked him a lot of very specific questions. To his credit, he was honest in saying that it wasn’t currently running well, despite the new parts. He also was honest in saying that he didn’t know much about tractor engines, so he wasn’t sure what was wrong. A mechanic friend of his was able to get it running a few months prior, and it had run strong when he bought it two years ago. I consulted with a friend of ours who is a tractor mechanic by trade, and he agreed to go with us to look at it. As luck would have it, he also had the trailer we’d need to bring it home if we decided to buy it. The tractor was located on an island some distance away, and it seemed silly to drive down, look at it, and drive home again without a way to get it home. So the date was set for us to travel the 1.5hrs and one ferry ride to visit the tractor, along with the trailer we’d need if we decided to buy her. To say that I was nervous would be an understatement.

When we got there, it was a cold misty day with rain threatening. We’d already had rain off and on during the drive and during the ferry crossing to the island. But the weather held off while we checked over the tractor. Our mechanic put a practiced hand to the wheels, the steering, the gear shift, feeling for wear, rough movement and sloppy fit. So far, so good. We tried to get the engine started, and true to the owner’s word we could get her going but we couldn’t keep her running. A series of tests later, we determined that the distributor points were arcing and the carburetor was desperately in need of cleaning. We cleaned the points as best we could while standing there, and manipulated the carb’s air intake manually. We got her started, for awhile. Long enough to conclude that the engine ran strong but the problems were in ignition and fuel flow. Was it enough?

The mechanic and I conferred, and he said for her age she was really in remarkably good shape. The issues we were having were probably relatively simple to solve - a good carb cleaning and new points would probably make a world of difference. The tractor owner, again to his credit, had stayed out of our way during the two hours we’d spent working on the tractor. He was patiently waiting in the house for us to make our decision. But finally the decision came to me - offer him his asking price, offer him a reduced price, or say “no thanks”? Our mechanic suggested that the asking price was already well below market value, and the new parts could easily pay for the time required to work on the carb and distributor. He suggested I knock a certain amount off the asking price since she wasn’t running well, but still offer most of the seller’s asking price. My husband and I agreed, that seemed to be the best course of action. The moment of truth had come.

My husband and I walked down the driveway to where the seller and his father were waiting in the house, staying out of our way. We told him of our findings, and I think I probably kicked my toe at the deck boards while I spoke, and while I worked up the nerve to offer him most, but not all, of his asking price. Then finally I said that since we couldn’t get the tractor running smoothly, yet we thought we knew what the problem was, we wanted to offer him our best-offer reduced price. The moment between my offer and his answer seemed to take forever. But in that next instant, I was very relieve to hear “Deal!” I gave him cold hard cash out of my jeans pocket, which had been staged there for that very moment. My hands were shaking and I had broken out into a sweat. But the cash changed hands and the deal was done. And then I asked him the even more obnoxious question - would he help us load it up? He laughed and said “Sure!”

Over the next hour, we pushed and pulled and coaxed and banged up knuckles but finally got the old girl loaded into our mechanic’s trailer, with only inches to spare on each side. We loaded up all the extra parts, including a carb rebuild kit and a pair of new front tires. We repacked all the gear that our mechanic (bless his heart) had brought down with him for her diagnostic session. And then we hit the road. About five minutes after we pulled out, it started to rain.

The drive home was easy enough, and we got the old girl unloaded at our mechanic’s workshop with about 20 minutes to spare before nightfall. During the ride home, we’d decided that she’d stay at the mechanic’s house while I got her carburetor cleaned up, and that we’d buy new distributor points and a resistor for her electrical system. We certainly have some work to do on our old girl.

Perhaps I need to eat a little crow for being so quick to dismiss the idea that we’d ever own a tractor. They are simply too versatile, and we have too much to do, to have dismissed the idea so quickly. It took awhile to find “the right one”. But I’m convinced after our mechanic’s very thorough check that we’ve gotten a strong little tractor who will be able to help us with our various farming and forestry work in the years to come.

PS - given that she was manufactured in 1939, the year that the classic “Wizard of Oz” came out, we have named our tractor Dorothy - a solid, likeable, humble yet ambitious American farm girl. The name seems to fit her quite well.

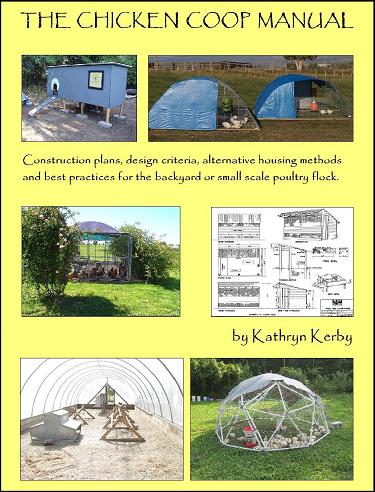

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

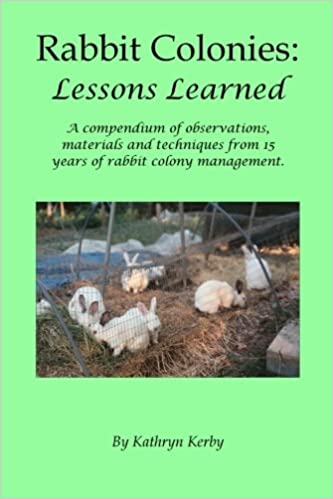

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.

Weblog Archives

We published a farm blog between January 2011 and April 2012. We reluctantly ceased writing them due to time constraints, and we hope to begin writing them again someday. In the meantime, we offer a Weblog Archive so that readers can access past blog articles at any time.

If and when we return to writing blogs, we'll post that news here. Until then, happy reading!