When is a Farmer, A Farmer?

January 30, 2012

While researching this blog entry, I found myself wondering how to I could possible condense all the different variations of a farmer, into a single image. I was digging around online, just sort of looking at the possibilities, when I stumbled across a blog entry talking about the documentary film The Real Dirt on Farmer John, about the life of Illinois farmer John Peterson. This film has won a number of awards for its description of one man’s attempts to remake his family farm. His efforts not only saved the farm, but subsequently helped chart an entirely new course for sustainable agriculture as well. Here is one individual who certainly deserves the title “farmer”. The blog entry where I found the photo is called the Sustainable Table Chronicles, and is very worthy of some reading time.

I have wrestled with the question of whether I’m a farmer. For most of my life, I’ve worked with either plants and/or animals - breeding and propagating them, raising and cultivating them, managing different populations, harvesting them, building infrastructure to nourish them. For most of that time, I either did that work on my own, without pay, as a hobby. For some of that time, I was paid by others to help them manage their animals, plants, farms and/or ranches. In the last few years, I’ve been building my own operation and starting to get paid for what I have produced. Sometimes I have been paid very well. Sometimes that pay hasn’t been so good. And over the last few years, my off-farm income has declined while my on-farm income has grown. This year, for the first time, it looks like the vast majority of my earnings will be farm-related. But does that qualify me to be a farmer?

As I have described my work to others, their interpretation of my job title has been all over the map. Some have declared me a hobbyist, because our operation isn’t big enough in their eyes to qualify as a “real” farm. Some have said our operation is too big, and we should cut back because I’m not a farmer and never will be, thus I’m wasting time and money pretending to be one. Some have declared that no matter how big we are, we’ll never be farmers on a farm until we have certain items, objects or features - a barn, a tractor, cows, row crops, employees, etc. And some have avoided calling us farmers because they consider it an insult, a lowly job title that we’re too good to have. My accountant has called us a farm for a number of years, and we’ve either filed corporate returns or a Schedule F to declare our earnings in various ways. Oddly, the IRS seems easiest to convince of our “farm-ness”.

I have slowly but surely warmed to the idea that I can legitimately call myself a farmer, for a variety of reasons: I spend more and more of my time building and improving a property (now two properties, since we’re leasing land), for the sole purpose of raising and selling various agricultural products as a result. I’m earning more and more of my income that way. I am gaining skill and experience and good judgment on what works and what doesn’t, while building and running those agricultural operations.

But somehow, for me the title “farmer” is still elusive, because it’s a badge of honor that I don’t quite feel I’ve earned yet. I don’t have my markets figured out. We haven’t yet sold our first batch of market hogs (psst, buddy, wanna buy a pig?). I don’t have my field rotations nailed down yet. And I’m still refining my next-generation animal barn design. So at what point do I become a farmer?

Maybe it’s like trying to identify when we first become adults. We have to work in that capacity for awhile before we can finally look back and say “aha, I’ve been an adult now for awhile.” Perhaps in the future I’ll look back on this time and decide that yes, by this point I was already a farmer, and already farming, even if I didn’t quite have all the details figured out yet. And for true professionals of any breed, the best of the best often say that their profession is challenging specifically because there is always something else to figure out. At which point it becomes not only a science, but an art. So perhaps I’ll always be in the process of "becoming" a farmer. Or, perhaps I should say I'm a practicing farmer, like a doctor practicing medicine or an attorney practicing law. Most of the best job descriptions I’ve known included that aspect of always learning something new. Farming certainly does.

I guess I can’t say for sure yet that I’m a farmer. I think I’m becoming more and more of a farmer, every single day. Lest I leave the term still too loosely defined, in closing this entry I’ll share one of my very favorite definitions of a farmer, and of farming, courtesy of Paul Harvey. Thanks, Paul, for providing such a wonderful definition of this multi-faceted profession.

So God made a Farmer

By:Paul Harvey

And on the eighth day, God looked down on his planned paradise and said "I need a caretaker."

- So God made a Farmer

God said "I need somebody willing to get up before dawn, milk the cows, work all day in the field, milk cows again, eat supper then go to town and stay past midnight at a meeting of the school board."

- So God made a Farmer

"I need somebody with arms strong enough to wrestle a calf and yet gentle enough to deliver his own grandchild; somebody to call hogs, tame cantankerous machinery, come home hungry, have to await lunch until his wife's done feeding visiting ladies, then tell the ladies to be sure and come back real soon, and mean it."

- So God made a Farmer

God said "I need somebody willing to sit up all night with a newborn colt, and watch it die, then dry his eyes and say 'maybe next year'. I need somebody who can shape an axe handle from a persimmon sprout, shoe a horse with a hunk of car tire, who can make a harness out of hay wire, feed sacks and shoe straps, who at planting time and harvest season will finish his 40 hour week by Tuesday noon and then, paining from tractor back, will put in another 72 hours."

- So God made a Farmer

God had to have somebody willing to ride the ruts at double speed to get the hay in ahead of the rain, and yet stop in midfield and race to help when he sees first smoke from a neighbor's place.

- So God made a Farmer

God said "I need somebody strong enough to clear trees and heave bales, yet gentle enough to wean lambs and pigs and tend to pink combed pullets; who will stop his mower for an hour to splint the broken leg of a meadowlark. It had to be somebody who'd plow deep and straight and not cut corners; somebody to seed, weed, breed, and rake and disk and plow and plant and tie the fleece and strain the milk and replenish the self-feeder and a hard week's work with a five-mile drive to church. Somebody who would bale a family together with the soft, strong bonds of sharing; who would laugh and then sigh, and reply with smiling eyes when his son says he want to spend his life doing what Dad does."

-So God made a Farmer

Digging Out and Cleaning Up

January 20, 2012

The remains of one of our hay sheds. Ironically, the hay shed shielded the shelter behind it from getting as much snow as it would have otherwise, yet that stick-built shelter would have withstood the weight better. We have some stick-built shelters, and some portable shetlers like this one. This one lasted for 10 years and countless storms before finally collapsing. In terms of cost effectiveness, that's pretty good performance. In terms of wear and tear during storm events, such inexpensive construction starts to cost quite a bit. So we'll be replacing it with sturdier construction.

Weather in the Pacific Northwest is generally pretty mild. But every once in awhile, we get a doozy of a storm, or a series of storms, which wreak havoc on the farm. The last time we suffered severe storm damage was May 2010, when a huge cottonwood fell during a windstorm, and clipped the corner of the house. Prior to that, we’d had a variety of snowstorms which came and went without too many problems other than me outside shoveling snow off the shelter roofs anytime we had any snow accumulations over 3”. But that precaution spared us any major damage from snowfall. Until now.

We knew that we had two snow events coming well in advance. The first wasn’t due to dump too much snow on us, but it would set the stage for a stormy week of cold temperatures, windy conditions and the possibility of additional snow accumulations throughout the week. That was due to start late Saturday night, January 14th. So we spent most of Saturday running errands and stocking up on supplies, in case we were snowed in. Unfortunately, the snow arrived early and came down fast. We were still 10 miles from home, fully loaded with hay and feed in both trucks, when the snow started to accumulate as the sun went down. Suddenly, we had some serious driving conditions to contend with. A trip that normally would take 15 minutes on clear roads, ended up taking 2 hours with both our trucks in four wheel drive. That includes reaching hills that were impassible, and turning around to go another way. We were stressed out, wet, cold and exhausted by the time we got home. During our trip home we passed a variety of vehicles that had gone off the road or had spun out on the quickly deteriorating roads. Wow, we were glad to get home safely.

The weather continued to deteriorate. Instead of getting a “dusting” of snow that night, we had 4” by bedtime. I was on snow watch that night, so I got up periodically to check how much snow had come down. I had already shoveled snow off the shelters when we got home that night, but I had to be ready to do it again if we had a lot more snow overnight. Thankfully that didn’t happen, so I was able to get some sleep. Sunday dawned to on-again-off-again additional snowfall, but no major new accumulations. Yet we had more snow due during the day Monday, and throughout the week. We waited, and watched.

The next four days came and went, with spats of snow falling throughout the week. The next major snowfall occurred Wednesday, bringing us to a total of 12” of snow. That’s a fair amount for this area, and roads were a mess despite county road crews working around the clock. The growing snow load on power lines and tree branches caused a number of short-lived power outages, and we ended up using our lanterns and oil lamps frequently through the week. Steve did go to work Monday morning but he came home early Monday afternoon, and stayed home for the rest of the week. But supposedly we were done with the major snowfall by Wednesday evening. We had hopes of getting out Thursday.

Thursday dawned with light snowfall. Once again the roads were impassible, but the forecast called for the snow to stop in mid-morning, and temps to start rising rapidly that afternoon. We waited, and watched. But the weather apparently didn’t read the forecast, and we watched as another 6” fell during the day. Apparently, the new warm air mass was stalled just south of us, generating something of a snow engine which just kept dumping more snow on us. Worse, the folks south of us got just enough warmth from the new air mass that they warmed slightly above freezing, but the old air mass was still chock full of moisture, and they got a heavy dose of freezing rain for 12 hours. The damage to those areas was incredible, with whole trees coming down throughout the area. Our livestock mentor and one of our major rabbit customers both suffered heavy damage from that event. So as much as we hated to see more snow come down, we preferred that to a buildup of ice.

Finally, Friday dawned with partly cloudy skies and no new snow. Temperatures finally started coming up, and we knew our marathon was almost over. We had 16” of snow on the ground. Happily, most of our shelters were OK, mainly due to all the roof clearing we’d done during the week. However, two shelters which had never needed clearing before were finally claimed by the snow - our hay shelter, and one of the dog shelters. Happily, the dog was not harmed - she was safe in her doghouse at the time, but she did look rather alarmed when peeking out from under the snow-covered wreckage of her dog run. We were able to get that roof cleared off and replaced in fairly quick order. But our hay shelter was a total loss.

There’s a phrase that “some days, you get the bear, and some days, the bear gets you.” This week, we feel like we argued with the bear and came away with only a few scratches. Having the hay shed come down was a loss, but I’ll take that any day rather than one of the main barns coming down. And had we been just a little further south, we might have had considerably heavier damage. Another phrase goes “you rolls your dice and you takes your chances.” We definitely got lucky this time, with this particular roll of the dice. As we replace our hay shed, and gradually replace our other animal shelters and barns, we’ll keep this last week in mind. Our future shelters will be built to withstand less fortunate weather.

Saying Goodbye to an Old Friend

January 10, 2012

Carmel a few years ago, after I accidentally woke her up from a nap in the summer grass. She was named for her round, chocolate-brown eyes that reminded me of little caramel candies. Her personality was as sweet as those candies, but she had a wicked sense of cunning to get what she wanted.

We had to say goodbye yesterday to an old friend, my 15 year old dog Carmel. She finally died of old age, after a long and I’d like to think a happy life. Some would think it silly, foolish or simply a waste of time to get all emotional about a dog. Others know exactly what I’m talking about without further explanation.

I adopted Carmel as a 10 month old puppy. She was my first rescue, from a "bought-her-for-the-kids" forgotten backyard ornament situation. She was dreadfully overweight, an odd combination of timid + gonna-do-things-my-way-anyway, and she had no manners whatsoever. Her first training session came the night I brought her home, when she tried to jump on the dining room table to eat our just-delivered pizza. That was my very first moment as Alpha Dog, and it wasn't pretty. But she trained up amazingly well despite me making every possible mistake with her that a well-intentioned-but-uninformed person could possibly make. And I continued making mistakes with her throughout her life, but she liked me anyway. Some days I wasn't entirely sure why. But it was her patience and devotion and occasional conniving ways (think 'old age and treachery') which gave me the skillset, patience and confidence to go work with the bigger, sometimes easier Anatolians.

Last night I didn't need to put the dog gate up across the kitchen door to protect against midnight raids. I didn't need to listen for the sound of dog toes tiptoeing across the living room and down the hall to sneak into the kitty litter box. I didn't need to let anyone out at midnight with a flashlight for one more potty break in the rain, and there was no one waiting patiently in front of the heater this morning, looking forward to that first welcome burst of warm air. The house is entirely too quiet, despite the presence of four whiny, self-absorbed, spoiled, utterly psycho cats. I still have little dust bunnies of black fur in various corners of the house, which would magically re-appear within hours of vacuuming. I actually debated with myself whether I should leave them there. And I can wash for the last time the doggie towel that has lived by the back door, waiting to dry off the black dog as she comes in from the rain. It's been 15 years that we've had a dog in the house. I'm not entirely sure what to do with a dog-sized hole in the universe. But I take comfort from the idea that she's running and playing now with all our departed friends.

We may bring one of our outside doggies inside. Or we might experiment with having a dog-free house. Keeping up with housework and laundry would certainly be easier. But I think one of the things I'll miss the very most is coming home from being out and about, and going in to the bedroom, to see that our deaf old dog had pushed open the bedroom door yet again and was fast asleep on our bed, so that she could be near us even when we weren't home.

I told her spirit last night to come back from the great beyond and give me a hard bite whenever I'm about to do something stupid with one of our other dogs. But maybe she's already doing that - one of her toys was mysteriously in the hallway last night, hours after her departure, and we have no idea how it got there. And there was a suspiciously dog-sized depression on the bed at bed-time last night. Carmel, wherever you are, I hope you keep up your sneaky old-dog tricks. Please drop by to say hi once in awhile, when you're on a break from playing with all our departed friends.

2012 Feed Bill Challenge

January 1, 2012

A western Washington farm scene with traditional barns and silos, one of which is missing a roof. These silos were originally built to store feeds (typically corn or small grains) produced on the farm. The silos provided year-long storage, such that the grains could be fed out to livestock a little at a time until the next grains harvest came in. These silos are still considered an icon of American agricultural production. Yet many stand empty today, since many small-scale farmers no longer grow their own feed. Here's to having full silos again, and local farm communities who can and do produce their own feeds. Photo taken by

Sally of Chicken Dance Ranch in the Okanogan area of Washington state, where growing feeds is still a vital agricultural activity.

Here at the start of a new year, I’ve started a new project on the farm. I’m calling it the Feed Bill Challenge of 2012.

Most livestock owners are woefully aware of how big a chunk of cash it can be, to keep our furbearing farm citizens in good flesh. There’s a reason many kinds of livestock are called “hayburners”, either affectionately or otherwise. But woefully few livestock owners (myself included) have really made a dedicated effort to look for ways to cut down on that feed bill. I’ve heard more reasons for NOT doing so, than seen examples of trying to do so. And let’s be frank here. It’s easier to just go to the feed store, shell out the bucks, and load the feed than it is to get creative about cutting down on that bill. There’s also something of a social stigma about being frugal with our money. At least there used to be a stigma; nowadays that is lifting somewhat for a lot of families. Or perhaps more accurately, a lot of families are looking that situation square in the eye and saying “either we cut the bills or we reduce the herd”. The former might be a challenge, but sometimes the latter is more of a challenge for a variety of reasons. So I’m definitely not the only one asking these questions. But I’m going to make my current and future feed costs public, so that folks can see exactly what we’re spending on it now, and how we find ways to reduce that cost over time. It’s going to be embarrassing, I’m sure. But I think it’ll be educational, and I really hope it paves the way for other folks to go through the same process and find their own ways to cut their particular feed bill.

Now, some ground rules:

1) The goal here is to cut the bill without reducing the nutritional intake of what we’re feeding. So simply getting cheaper feed isn’t going to cut it. I have to preserve the high standard for feeding, while simultaneously cutting costs.

2) Another of our goals, which I’ve written about before, is to eventually raise our own feed. So the feeds that we use must be feeds that we can ultimately, cost effectively, grow ourselves.

3) That leads to a third issue - we want to really point out the fallacy of relying on feeds that are grown far away. Small grains were once produced here in profusion to feed our nationally-known dairy herds. Yet the advent of cheap transit resulted in those small grains being grown elsewhere. Now hardly anyone here is growing small grains, let alone teaching other folks how it’s done. While feeds produced in the grain belt might be “affordable” in the sense of bulk purchasing, they are NOT affordable in terms of the distance they travel and all the infrastructure that must be supported to enable that transit. That practice has also led to the loss of the local knowledge base for how to successfully grow fodder crops. By focusing our attention on locally grown feeds, we support not only those growers, but also that collection of local know-how.

Now, in the category of how to cut costs, we have several different options to pursue:

1) reduce the amount actually fed out - this can be accomplished by reducing waste either before or during feeding (for instance, hay spoiled because it’s been rained on or trampled underfoot), choosing feeds that offer greater utilization when ingested (for instance, using sunflower seeds as a potent source of both protein and fats, rather than buying in separate forms of both protein and fat), or using feeders that encourage healthy feeding behaviors without also inspiring “food stealing” between animals, such that some animals get too much.

2) Find cheaper ways to buy feeds - this is where I think we’ll make some of our biggest strides right away. Buying feed by the bag at the feed store is THE most expensive way to feed an animal ever invented. We’re paying the ultimate retail price for something that is raised as a commodity. Simply buying in bulk direct from the grower can save dramatically over buying the same thing, in small quantities, from the local feed store.

3) Find cheaper ways to bring home and store feeds - right now we’re going to the feed store 2-3 times a week, and making a separate trip to our hay grower 2 times a week. That is time and energy I could be using to MAKE money, not SPEND money. Furthermore, it’s more wear and tear on a vehicle which I need to maintain. So finding ways to move more feed per trip, cost effectively, is on the list. Even harvesting our own feed, which we only dabbled with last year, involves planting, soil-working, and harvesting equipment. While we will save money to put up our own hay rather than buy it in during 2012, we can save even more money by having our animals do as much of the planting, cultivating and harvesting work as possible. This gets into rotational grazing management, which will require its own investment of time and effort. But most of the folks we’ve talked to can show a very definite savings over the costs associated with conventional tillage and harvesting.

4) Find cheaper ways to grow feeds - One of the core concepts for sustainable farming is the notion that we should be finding ways for plants to grow in ways that keep them, and us, happy. For instance, putting alfalfa in a cold damp climate, then driving off pest and disease issues with tanks of chemicals, is not sustainable. Planting a locally-appropriate clover in that same field might give lower overall yields, but it won’t require the same costly intensive care to bring to harvest. At the end of the day, that lower yielding clover might be cheaper to feed and healthier for the animals, for us, and for the local soils and waterways since we won’t have to use such harsh chemicals just to bring it to harvest.

5) Find cheaper ways to provide feeds from year to year. Many of our most popular feeds are annuals - sunflowers, corn, soy, most small grains, and fodder roots such as mangels. Many growers simply buy in the seed they need for each growing season. Can’t beat that convenience, but it’s costly. It also leaves us vulnerable to the whims of the various seed companies - if we love one of their varieties, and they discontinue it, where does that leave us? Saving seed such that we can harvest one year to plant the next will take some fodder growing areas out of production, at least in terms of this year’s harvest. But it’ll reduce the overall cost of feed next year because those seeds won’t need to be bought in. Furthermore, many livestock species can make much better use of either wild or cultivated perennials. Permanent pastures, wild self-seeding forbs, either wild or cultivated hedges and lees, and cut-and-come-again type plantings can give us months if not years’ worth of feed value, where before we’d just harvest the whole thing and be done.

This will be an ongoing process, this business of cutting down on the feed bill. And I’m sure there are some categories/methods which I haven’t even thought of yet. But it’s a worthy pursuit, because it makes improvements on so many levels to our operation. Stay tuned, Dear Reader, as we move forward with this project. I’ll post our January feed costs at the end of this month as our “starting point”, then each month or so I’ll talk about a different approach for reducing that cost. At the end of the year, I’ll compare what we used to pay for feed, with what we’re paying for feed after those various changes have been made. I don’t know where we’ll end up, but I’m aiming for at least a 10% reduction in feed costs per head. Here’s hoping that we not only meet and surpass that goal, but also that we inspire others to take the Feed Bill Challenge with us.

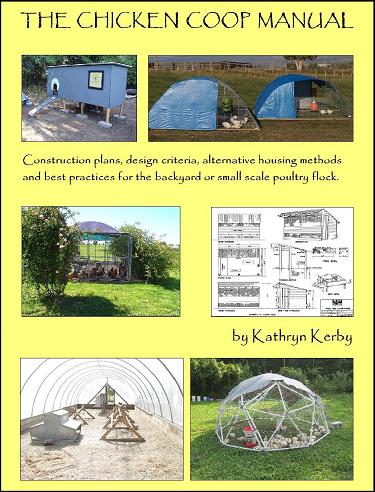

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

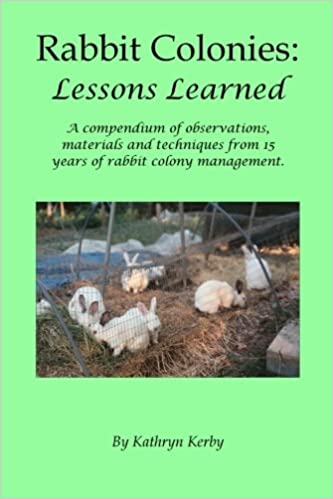

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.

Weblog Archives

We published a farm blog between January 2011 and April 2012. We reluctantly ceased writing them due to time constraints, and we hope to begin writing them again someday. In the meantime, we offer a Weblog Archive so that readers can access past blog articles at any time.

If and when we return to writing blogs, we'll post that news here. Until then, happy reading!