Predator Control

January 30, 2011

During the wee hours this morning, one of our three livestock guardian dogs sounded off. Within a few heartbeats, the other livestock guardian dogs had added their barking to the song. Which could only mean one thing - something was on the farm that shouldn't be. I hastily put on some clothes in the dark bedroom, stumbled to the back door, shoved on my mudboots and thankfully remembered to grab a flashlight. While I had been putting on clothing, the dogs not only continued to bark but all the chickens began sounding off with alarm calls of their own. About 90 seconds after I'd first heard the dog barking, I was outside. But the action was over. Whatever had been there was gone. I stayed outside for a few moments to make sure all was well, and I visited both the bird coop and each dog, to make sure they knew I'd heard them and I was checking everything. I went back inside and crawled back into bed. It was 2:10am. No birds harmed, no damage done, nothing lost except about five minutes' worth of sleep. Which is as it should be.

Predator control is a thorny and persistent topic amongst livestock owners. The various livestock email groups I participate in will periodically have some desperate message asking how to prevent predation, posted by someone after a sleepless night of warding off predators. Or worse, after a disturbing morning of going out to do morning chores and finding shredded bodies instead. It is never a happy conversation. But it is a frequent conversation, and one with the same lessons to be taught each time.

Most folks get started with livestock without a great deal of forethought about predators. I think there's a natural "that won't happen to us" mentality. Not because people are dumb, and not because people don't do their homework. Rather I think it's human nature. We get into livestock hoping for the best, and raids by predators are not a part of that "hoping for the best" mentality. Yet sooner or later, those predators come calling. More accurately, they come visiting several times to check things out, test the boundaries, assess the risks prior to making their attempt. If it sounds like I think predators are smart,

that's because they are. First rule of combat - never underestimate your opponent. There's a fair amount of documentation that predators will carefully check out a property before making their first strike. We're already behind the curve before we even know there's a problem brewing.

The owner's typical first knee-jerk reaction is to want to kill the predator. That seems to be poetic justice sometimes, particularly after finding beloved animals disemboweled out in the paddock or pasture. Yet that "kill the predator" strategy has several flaws. First, the owner must actually find the predator. Most predators have territories that they traverse on a regular basis, and that predator could be miles away just a few hours later. Or the owner could wait until the predator comes back, which sometimes happens within 24 hrs. But that predator can see or smell their presence and doesn't give them the opportunity to take that shot. The predator will go back to watching and waiting, and not moving until it's safe to do so. At which point the owner still has a problem - livestock at risk of additional predation.

A bigger, and much more realistic threat is very rarely considered in the first few days and weeks after a predator loss. Even if the predator is dispatched, the livestock are STILL not safe from predation. Why? In any given area, any particular species is not represented by only one or two or three individuals, but rather by an entire population. And each individual in that population is constantly working to improve its situation. For predators, that typically means hunting territories that are defended against others of the same species. That coyote you spotted three days ago trotting across your pasture has a

territory that it marks, and defends, against transgressors. That red tailed hawk that circled overhead has a nest nearby, and it will defend its territory against other red-tailed hawks. So when we take out a troublesome predator, that's not the end of the problem. Rather, that's an invitation for all the neighboring predators to begin competing for that newly available hunting territory. And typically, several individuals will compete for a single recently vacated territory. So where you had one coyote hunting yesterday, after shooting him you'll have laid out the welcome mat for six neighboring coyotes to come in

next week. Your troubles have only started.

We have taken a different approach - the same approach that police departments give homeowners after a burglary. Look at your operation through the eyes of someone, or something, trying to get in to take what you have. Then make it as difficult to get your stuff as possible. First, we are firm believers in good tight fencing, and a roof over the smaller animals. We typically use 4' high field fence, positioned about 6"off the ground, with hotwire at the top, and sometimes the bottom. Secondly, we only day-range our animals, and we don't range our young animals at all. We bring pregnant at-risk animals inside or into smaller quarters. We keep lambs and kids and chicks under cover and away from both terrestrial and avian predation.

Third, we have acquired several livestock guardian dogs. Contrary to common ideas about livestock guardian dogs, their first role is not to fight off or kill intruders. Rather, their first job is to warn off would-be trespassers by barking. If that doesn’t work, then the try to chase off the intruders. If that fails, only then will they actually fight. They are very well matched against most predators that are common on the North American continent, even to warding off bears and big cats, or coyote packs.

The only reason I was able to go back to sleep this morning is because I knew what had probably happened. A predator had come by, perhaps not for the first time, and had gotten close enough, and inquisitive enough, to catch the attention of at least one dog. Once the first dog started barking, all the others were "on" and looking for the source of either the smell or sound that had tipped them off. Yet it was the combination of dogs and fencing which had prevented the predator from making a quiet kill and a quick getaway. A meal here would simply be too much effort to get through the fence, and too much risk because of the dogs. The predator moved on without so much as a bird's feathers out of place. The fencing had done its job, the dogs had done their jobs. So the only job I needed to do was double-check the perimeter, congratulate the dogs, then happily go back to bed. That's really the best recipe we've found so far for predator control.

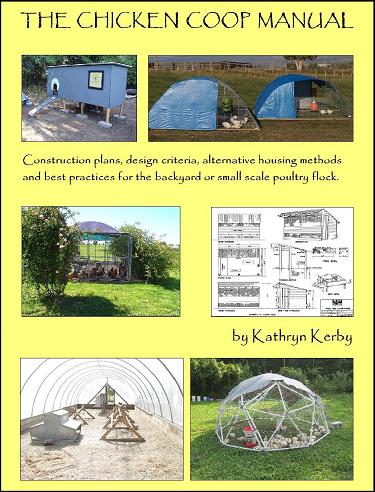

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

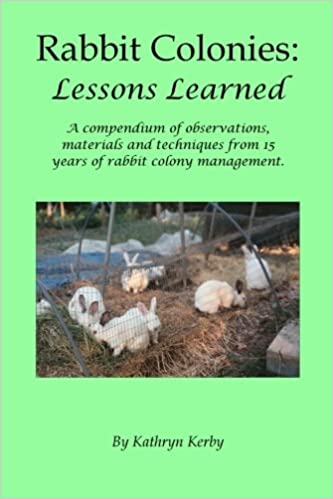

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.

Weblog Archives

We published a farm blog between January 2011 and April 2012. We reluctantly ceased writing them due to time constraints, and we hope to begin writing them again someday. In the meantime, we offer a Weblog Archive so that readers can access past blog articles at any time.

If and when we return to writing blogs, we'll post that news here. Until then, happy reading!