|

Search this site for keywords or topics..... | ||

Custom Search

| ||

Is Michigan Really Outlawing Farm Hogs?

March 28, 2012

Are these feral hogs, or domestic hogs? Here in the state of Washington, they are standard farm hogs, living in forest paddocks, completely legally. If they were living in Michigan, their status would be uncertain right now. The folks in MI are wrestling with a new state law that seems to be throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater. Jury is out on what the decision will be and how it will affect the MI hog industry.

A few months ago, we started hearing some very odd stories about a new law in Michigan, regarding feral hog control. The first hints of this story came in the form of borderline hysterical or alarmist emails that went out to several of the different livestock and farming email groups that I subscribe to. The emails made wild accusations that the MI state government was going to start shooting hogs even if they were on farms. Other emails claimed that the state was adopting Nazi-type tactics about being able to search farms without a warrant, to find and destroy certain breeds of hog. While the Internet is fabulous at helping to disseminate information, it’s just as capable of disseminating mis-information. So when those types of emails come across my desk, without any supporting documentation or reference to an actual law or legislative bill, and particularly if they are merely quotes from some editorial commentary, I generally ignore them.

Then I started to see some of our small scale hog producers on one of the hog lists talking about the new MI policy. And this time, they provided more solid information, with references. The MI Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) had added several species to the state’s Invasive Species Act, which would give the state the ability to forbid ownership of those species and control (or eradicate) existing populations. The amendment would go into effect April 1st, 2012. Wild/feral hogs were included in that list. But because the amended Invasive Species Act language didn’t specify the differences between domestic hogs and wild/feral hogs, a group of MI livestock owners asked the MDNR to clarify the criteria to be used to make that determination. The MDNR replied by providing a final ruling in December, 2011, which listed the criteria.

The original wild/feral hog description from the amended Invasive Species Act reads: “Wild boar, wild hog, wild swine, feral pig, feral hog, feral swine, Old world swine, razorback, Eurasian wild boar, Russian wild boar (Sus scrofa Linnaeus). This subsection does not and is not intended to affect Sus domestica involved in domestic hog production.”

While the summary in general and the last sentence in particular would seem to rule out domestic breeds, the final ruling and subsequent statements from the MDNR have actually made the situation more confusing. The final ruling referenced a list of criteria developed by John J Mayer and Lehr Brisbin, two wild/feral swine researchers working for decades in South Carolina. Their list of common wild/feral swine features was included in the MDNRs final declaration, to definitively answer which hogs would be considered feral, and which would not.

Per the MDNR, any hog having one or more of these criteria could be considered feral and thus subject to the new amendment:

1) bristle tips which are lighter in color than the rest of the bristle shaft

2) dark “points” coloration, ie, dark-colored snout, ears, legs and tail, and lack of light-colored tips on the bristles

3) Coat color combinations including wild/grizzled, solid black, solid red/brown, black and white spotted, black and red/brown spotted

4) Lighter-colored underfur than the overlying guard hairs

5) A striped coat pattern in juveniles (ie, piglets), typically a black spinal strip and three to four brown irregular stripes along the length of the body.

6) Tails which can curl, but are typically carried straight.

7) Erect ear structure, as opposed to floppy.

8) Undefined skeletal measurements (and because they are undefined, any hog could potentially meet them).

9) Other as-of-yet unknown criteria which will become known over time.

Here’s where folks were getting riled. For one thing, most domestic hogs would meet at least one of the criteria. So, how reliable are those criteria? Mayer & Brisbin first presented those criteria in a research article in 1991, then expanded on them in book form in 2008. Both the original article and subsequent book went to great lengths to describe each criteria, and how the criteria varied amongst specimens taken from the field. Their extensive documentation from the field provided plenty of confirmation that the criteria exist in wild/feral hog populations.

However, a crucial point was missed or ignored by the MDNR. In both works, the authors differentiated between three categories of wild swine:

1) purebred Eurasian Wild Boar (both male and female)

2) Feral Boar, both male and female, which the authors defined as escaped animals of domestic breeds, and

3) Hybrids created when Eurasian Wild Boar animals crossed with feral animals.

That description of the overall wild hog population should have, by itself, been sufficient to prove that domestic hogs share traits with the feral/wild hog populations. In fact, Mayer & Brisbin repeatedly pointed out in their article that feral hogs brought those domestic breed traits with them into the wild, and those domestic characteristics were found in the hybrid descendants of any wild hog/feral hog crossing. Indeed they went so far as to say “Therefore, it currently is possible to encounter wild populations that might vary from pure feral hog to pure Eurasian wild boar in composition.” So, by the authors’ own statements, the list of criteria was merely a summary of all the traits seen in the wild. Many of those traits came from escaped members of domestic breeds, and still exist in domestic breeds to this day. The list was never intended to differentiate between wild and domestic hogs. In fact, by the authors’ repeated examples of how domestic traits were seen in the wild, the list could never serve that purpose. From that point of view, the MDNR’s list of criteria is worthless for differentiating between the two, according to the very authors and research the MDNR cited as their authoritative source.

A second issue is one of semantics, and it seems a small point but it’s not. “Feral” has two different meanings in this whole topic. It can refer to a wild animal descended from parents born into captivity as standard pigs, but which at some point escaped captivity and reproduced. That is the definition Mayer & Brisbin used. However, standard English language usage would also define a “feral” animal as a captive animal of any breed which has escaped and is living on its own for any length of time. Both definitions acknowledge the potential for the captive genetics to contribute to the next generation of wild hogs. The MDNR amendment did not clarify which definition it was using - the captive pig which makes its escape, or the wild pig which happens to trace back to domestic breed parents. This concern is at the heart of many small scale hog owners’ objections to this rule. Any domestic pig could potentially become a feral animal in the future. Yet the vast majority of captive hogs never make that escape. If the rule’s intent is to prevent any additions to the wild hog population, are hog farms at risk of having all their animals destroyed, simply to prevent some possible future escape? That concern may seem far-fetched, but we’ll return to this question in a moment.

Third, a number of small scale pastured hog owners raised the point that the only hogs likely to be exempted from this new rule were those in confinement-style facilities. By definition, the more intensive the confinement, the less chance there is for them to escape and become feral. Suspicion quickly mounted that the state’s confinement hog industry was behind the new policy. More specifically, it was suggested that small scale pork producers who pasture their hogs were the ones in the gunsights for this new policy. Pastured pork production is gaining popularity as a cost-effective management strategy, and has a growing market share. While tiny compared to the volume of conventional pork sold in this country, some pastured pork producers felt this new rule was a thinly veiled attempt to outlaw their pastured operations.

While these last two concerns might seem paranoid, a letter from the MDNR’s Director Rodney Stokes to a group of concerned MI hog owners</a> would seem to deepen, rather than soothe, those concerns. In that letter, Director Stokes indicated that the state would use “existing information” to determine which farms and facilities were most likely to house, raise or otherwise own/manage hogs which might meet the wild/feral hog criteria. Any facilities which could have animals meeting the criteria would then be “a priority” for inspections, to ensure that any prohibited animals were not on the premises. Wait a minute, what exactly does that mean? Any hog, of any breed, could meet the criteria. So any hog farm would potentially have prohibited animals. And under the new law, any animals so found, even if they were on farm property rather than running at liberty off-property, could be destroyed under this new policy. By making that statement, the MDNR indicated that it intended to identify and destroy captive hog populations, apparently at its discretion.

So here we are, with a very puzzling situation. The state of MI says it wants to better control wild/feral hogs. Fine. As a result, the MDNR comes up with a list of criteria intended to identify those wild/feral hogs. Except that domestic hogs would also meet those criteria. But never fear, the state has assured farmers that the intent is to control wild/feral populations, not interfere with domestic hog production. Yet the MDNR has stated that its priority is to go to farms looking for animals which meet the criteria. If it found them, it has the authority to destroy them. We’ve already seen that most hogs would meet the criteria. So what’s stopping the MDNR from destroying most of the hogs in the state?

I searched for something in the MI state code which would give some kind of assurance that the above scenario wouldn’t play out. Specifically, what would happen if any given farm’s hogs simultaneously met the criteria, AND were being raised for domestic production. Given the issues listed above, most hog farms’ animals would simultaneously be both. Was there some protection in the code against domestic hogs being destroyed, simply because they could someday go feral? The amended language never stipulated that an animal actually had to be on the loose before it could be considered feral. Furthermore, as of this writing, Michigan state code does not specifically define “domestic hog production”, either in this particular policy or elsewhere. The closest the state comes to a definition is in its Animal Industry Act, which states that a domestic animal is a member of “those species of animals that live under the husbandry of humans”. Elsewhere in the MI state code, “feral swine” is defined as any hogs which “have lived their life or any part of their life as free roaming or not under the husbandry of humans”. Perhaps here was finally a relatively clear, functional distinction. If the animal is born and managed on the farm, MI state law would define it as “domestic”. If it were at liberty and fending for itself when found, state law would define it as “feral”. Yet the MDNR’s new amendment ignored the existing state definition of feral, in favor of criteria that also applied to domestic animals. And the MDNR went against its own promise not to interfere with domestic production, by specifically targeting farms raising those animals for domestic purposes. So the million dollar question becomes: was this new law going to result in destruction of hogs being used for normal everyday domestic farm production? The final declaration would seem to indicate “no”, yet Director Stoke’s letter would seem to indicate “yes”.

One possible way to clarify the situation and smooth some very ruffled feathers, was proposed by a number of small scale hog owners. The suggestion: restrict enforcement of the rule to those animals actually found running loose. It seemed a very easy way to protect the stated goal of the law, namely feral animal control, without endangering entire hog operations. That suggestion was, at the time of this writing, never commented on or responded to by the MDNR. By that silence, the contradictions and questions remain. As of the end of March, 2011, at least four separate lawsuits have been filed to block this policy from going into effect.

I can only shake my head and wonder at how this situation is going to play out. It would seem that the amendment is riddled with inconsistencies, overlapping definitions and contradictory goals. The letter of the law cannot possibly accomplish the spirit of the law. Such is the way it sometimes goes with regulatory code, unfortunately. What bothers me more is that folks who have stepped up to point out not only the problems, but also possible solutions to these problems, are apparently being stonewalled. Other regulatory efforts I’ve been involved with, either directly or indirectly, at least tried to minimize such contradictions, and find workable ways for folks to meet the criteria. That doesn’t seem to be the case here, which again begs the question of what the real intent is.

My only suggestion at this point, to the small scale hog owners in MI, is to keep fighting and keep working for a practical, rational compromise. For folks in other states, we’re on notice now more than ever, that we need to stay in touch with what new regs and policies are being developed which will impact our work. They don’t always make much sense, but it’ll be our job to fight them if and when they surface.

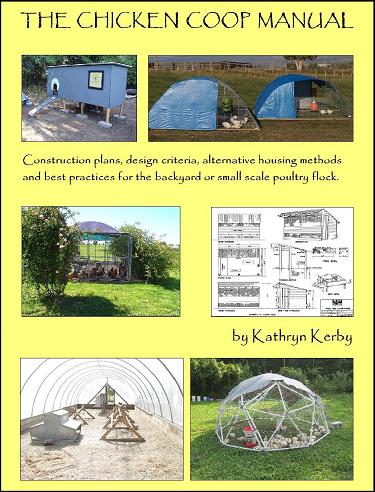

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

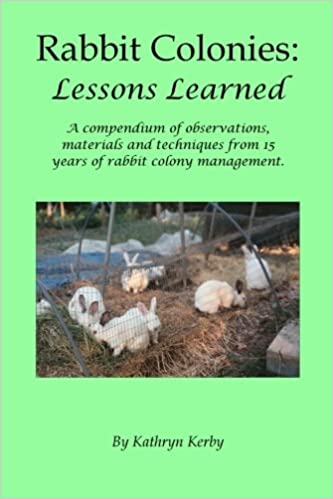

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.